Reading Credit, Financial Conditions, and Monetary Policy Transmission, the "preview" PDF from the AEA...

It's really good:

[We] study the influence of private nonfinancial credit in the dynamic relationship between financial conditions and monetary policy and macroeconomic performance in the U.S. from 1975 to 2014. Specifically, we examine the role of private nonfinancial credit in conditioning the response of the U.S. economy to impulses to financial conditions and monetary policy.

They want to see if high debt creates problems. Nothing is more important at this stage of the game. Nothing.

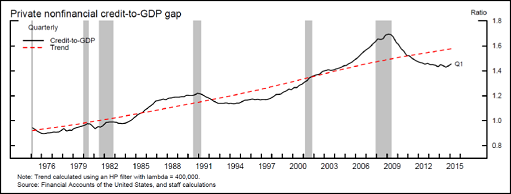

We use a broad measure of credit to households and nonfinancial businesses provided by banks, other lenders, and market investors. We follow conventional practice to measure high credit by when the credit gap (credit-to-GDP ratio minus its estimated long-run trend) is above zero...

That's what we looked at yesterday, how they figure the credit gap. I'm okay with it now. Sort of.

In addition to credit growth and the credit gap, they use a "financial conditions index":

Financial conditions indexes are summary measures of the ease with which borrowers can access credit.

A brief description:

To incorporate financial conditions, we construct a financial conditions index (FCI) combining information from asset prices and non-price terms, such as lending standards, for business and household credit, following Aikman et al (2017). In studies of monetary policy transmission, FCIs represent the ease of credit access, which will affect economic behavior and thus the future state of the economy.

Also:

Periods when the FCI is low (indicating financial conditions are tighter than average) are associated with worse overall economic performance: the unemployment rate is higher and rising, and real GDP growth is significantly lower...

And:

a positive impulse to financial conditions stimulates economic activity, but also leads over time to a build-up in credit and, ultimately, subpar growth.

You get the picture. So what did they learn from their study?

We find the following results. First, credit is an important channel by which impulses to financial conditions affect the real economy. We find that positive shocks to financial conditions are expansionary and lead to increases in real GDP, decreases in unemployment, and increases in the credit-to-GDP gap...

They find that policy works. But not always:

However, when the credit-to-GDP gap is high, initial expansionary effects dissipate but lead to further increases in credit, which, in turn, lead to a deterioration in performance in later quarters... When credit growth is sustained and the credit gap builds following looser financial conditions, the economy becomes more prone to a recession...

In a high credit environment, instead of getting more economic growth you get more credit growth and more recession. But it is not only pro-growth policy that is undermined by high levels of debt; restraint is undermined as well:

When the credit gap is low, impulses to monetary policy lead, as expected, to an increase in unemployment, a contraction in GDP, and a decline in credit. However, when the credit gap is high, a tightening in monetary policy does not lead to tighter financial conditions, as expected, and has no effect on output, unemployment, and credit...

In other words, a high level of debt makes policy less effective.

We test whether the transmission of monetary policy to forward Treasury rates differs significantly between high and low credit gap periods, and find there is less impact in high credit-gap states...

In other words, a high level of debt makes monetary policy less effective.

In addition, we evaluate whether the nonlinearities in economic performance may reflect factors other than credit, such as whether financial conditions are tight or loose, but find that the nonlinear effects are related to loose financial conditions only when credit is high, reinforcing our findings that credit has an independent role in explaining performance.

These findings are simply astonishing! Remember, it's not just some clown in the corner making graphs for his blog who is coming up with these things. It is people from the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve: central bank economists, saying things I would be happy to say. Things I am happy to repeat.

But then, they also say:

These empirical results can be useful for structural models that could link credit to financial conditions or monetary policy, and allow for nonlinear effects of shocks to economic performance based on credit.

Useful for making models? I was hoping for so much more: They want to see if high debt creates problems. Nothing is more important...

They point out that their result, their

empirical result ... supports the literature on the role of credit ... starting with Bernanke and Gertler (1989).

Since 1989. This is 2018. It's 29, almost 30 years they've known that a high level of debt (or credit, as the bankers call it) creates problems for the economy. Isn't it time to use these findings for something other than making models? How long do we have to wait for that to happen?

And there is one thing that I cannot get past. The last sentence in the last paragraph:

Taken together, our results suggest that theory and policy should address the role of credit in the transmission of monetary policy and financial conditions. In particular, economic dynamics of particular relevance to policymakers appear significantly different when credit-to-GDP has grown significantly faster than average for some time. This dynamic bears on the costs and benefits of using monetary policy to lean against the wind and prevent the buildup of credit (Svensson (2016), Gourio, Kashyap, and Sim (2016)). Moreover, it points to the benefit from additional research evaluating the potential for macroprudential policies to reduce the vulnerabilities associated with excess credit.

It's all good, right up to that last sentence, where the cat escapes the bag. They think it would be good to come up with "policies to reduce the vulnerabilities associated with excess credit."

Not policies to prevent credit from rising to the level of "excess credit". No no. Policies to reduce the vulnerabilities, so that we can have excess credit and not be so exposed to the troubles that it creates. They want to be able to expand credit further.

Dammit. They still think like bankers.