UNSNA is UN SNA, the United Nations System of National Accounts. Like NIPA. Except "NIPA" is pleasing to the ear, and "UNSNA" sounds like something you'd wipe off with a kleenex.

I googled

unsna data historical and found

System of National Accounts 2008 - United Nations ... so I went there looking for data. I clicked

DATA on their blue menu bar. That brought me to their National Accounts Data page. Text and links. At the end of the second paragraph is a link to

UNdata. That's the one you want.

I suppose I could eliminate the previous paragraph and just give you the UNdata link direct. But I'm trying to give you a sense of the struggle, perseverance in the search for data. (Plus, I write this stuff down so I can find my way back later.)

Anyway, the UNdata page has a search box, so now we're making some progress. I searched for

gross output. I got two hits. Two is good. What the hell am I supposed to do with 13 million hits?

I take

Table 2.6 Output, gross value added and fixed assets by industries at current prices (ISIC Rev. 4) because it has 91124 records. The other one (ISIC Rev. 3) must be older, and has half a million records. Maybe I'll look at that later.

Now we're getting to the meat. The Rev. 4 link gives me this:

The main body of the default page is a table of info about Armenia. It consists of several columns of info I don't want. But there are

select filters scrollboxes on the left. The first one is countries. So I can look at U.S. data instead.

Their scrollbar is neat. You just hover over the little down-arrow, and the list of countries scrolls, slow enough you can read it but not so slow that you're bored.

In the second filter box you can pick years for data. I want all the years, naturally.

Now the important part that you must not miss:

Just below the second filter list there is a link that says

More. You'll want to click that. It lets you zoom in closer to the data you want.

Click the MORE and you get two additional filter boxes. At the top of the third box is "total economy". That's the one I want. The other options are industry-specific. I want big-picture.

The last filter box lets you pick the data you want to see. That's a big deal. Basically, I wanted the first three that appear in the filter window, the ones I saw at Wikipedia yesterday: Gross output, intermediate consumption and gross value added (the last of these being approximately equal to GDP).

Oh, and most important, be sure to click the

Apply Filters link. It's below the last filter box. That's the magic that makes UNdata do what you want.

Oh -- funny thing. While writing this post I was going through the motions to verify the steps. But I didn't pick the country and the years before I clicked MORE. Then after I told you about all four filters, I tried to pick the U.S. and follow through the process. But the thing wouldn't let me pick the U.S. The list of countries scrolled down as far as the S's and no further.

I clicked LESS to go back to the two-filter screen and tried again. No good. But I refreshed the page, and then it worked okay. (In case you run into trouble using the thing.)

When I was done selecting my filter options I clicked APPLY FILTERS and the screen changed to show the data I wanted to see.

And if you don't know about CSV...

As the first of the UNdata screen-captures shows, across the top above the table of data are options including DOWNLOAD and SELECT COLUMNS. Both look useful.

I used DOWNLOAD, which gives some format options. First time, I tried XML. But when I loaded it into OpenOffice Calc I got a blank spreadsheet. So then I tried the "value separated" option identified as "comma" (Sheesh! What an awkward way to say

CSV) and it worked fine. Gave me a ZIP file.

Had to extract the data file from the zip before I could use it. (I just put it on my desktop along with everything else.) Then I right-clicked the data file and picked "open with" OpenOffice Calc. A "text import" window opened. I checked COMMA and unchecked TAB (or something like that) to make the sample import look right, then clicked OK.

OpenOffice Calc opened the file right away. Excel would be as easy, maybe easier.

Now we're getting to the meat.

I saved the spreadsheet right away, in spreadsheet format. Otherwise, it stays as a CSV file. And CSV files can't save the formatting that spreadsheets do, so the next time you open the thing most of your changes are gone. Save it in spreadsheet format, and you solve that problem.

I bolded the column labels in row 1, set column widths, and made the text in column C wrap automatically. (That's the kind of formatting you lose if you keep the file as CSV.) Then, because I wasn't careful with the import, I had to go into column F and delete a single-quote from in front of the number, on every row.

Also, I deleted some columns that UNSNA thinks important and I don't. Then I uploaded it to Zoho so you can see what the thing looks like. Here's the Zoho:

The filename was set by the UNdata exporter.

The first row identifies the columns. Look at rows 2, 3, and 4, column C. There you have output, intermediate consumption, and gross value added (all for 2011, as column D shows). The next three rows have the same three items of data for 2010. The rows continue like that, back to 1987. Then, from 1986 back to 1970 the only data item is gross value added. Before 1970, nothing.

Still, we've got three items of data for the years 1987 to 2011. Not a bad start.

The biggest problem I have now is that all the numbers are in column F. That means I can't copy a chunk of numbers and get just gross output or just intermediate consumption or something. I get a jumble. In order for the data to be useful, I have to separate it into different columns by type (so I get three columns of data rather than one) and also combine the three rows for each year into one row. Then I get ONE row for 2011 with three columns of data, and ONE row for 2010 with three columns of data, and ONE row for 2009 with three columns of data... I could go on, but I think you get my drift. It's obvious, isn't it?

So why doesn't UNdata know this? I think they DO know it. They're not stupid. Maybe they just want to make it difficult. Hey, I've never seen this data used anywhere. Why not? I think people are discouraged from using the data because it is so much work to undo the stupidities built into it by people who surely should know better. I'm beating around the bush here, trying to avoid being explicitly rude.

Oh, well.

If you scrolled the spreadsheet enough to see column F, you saw that the numbers are given in dollars. I mean, if the value is 27,170.5 billion, UNdata gives it as 27,170,500,000,000. That's not easy to read; you have to count digits. So I want to convert their numbers to billions. The numbers will be easier to read that way, and compatible with FRED's numbers.

That, and I want to convert the three-row-one-column format to one-row-three-columns, so the data is useful.

Now we're getting to the meat.

I copied the original data (Sheet1) to a new sheet to make the changes.

Figured out a calculation to move the data for me into the format that I want. It's in the first few columns of Sheet2 in

this Zoho file. (It only applies to the data back to 1987, where there are the three different values for each year. For 1986 back to 1970 I just copied and pasted the range of cells.)

Turns out that, like my column F values, my year values had the single-quote mark that left-justifies them and makes them behave like text instead of numbers. Next time I'll have to be more careful with the import from CSV.

I copied Sheet2 to make a new sheet and called it Sheet3. On the new sheet I copied the first few columns and pasted them as values over top of the calculations. After that I could delete the source data that was formatted badly, clean up the sheet, and credit

UNdata for the data.

And of course, they also present the data backwards, newest first, rather than chronologically. I sorted that. Here's what I have so far --

data now ready to use.

Now we're getting to the meat.

Now I was ready to

look at the numbers.

|

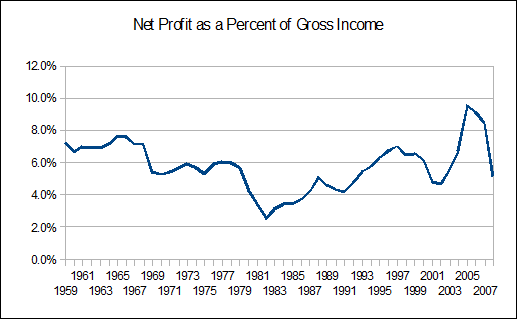

| Graph #1 |

I noticed

Wikipedia said

In the US economy, total intermediate consumption represents about 45% of Gross Output.

That's about right, for the blue line, since 1997 or so. More like 42% before that. And it looks like a trend of increase (for the blue line) and decrease (for the red).

Also... when you say "average" it suggests up-and-down variation, but it also implies

stability in the value. If intermediate consumption is trending upward as a share of gross output, it is deceptive to speak of its average value. Would be nice if the values went farther back in time, so one could be more certain about trends.

Now we're getting to the meat.

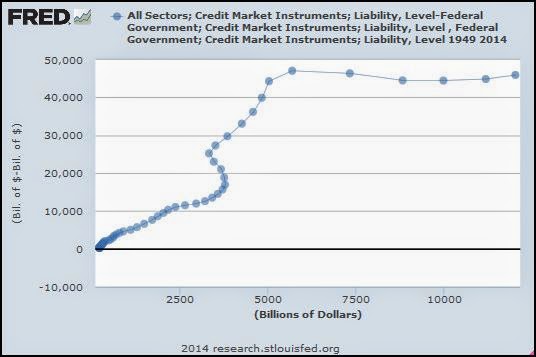

Another thing the Wikipedia article said was that "gross output" is what we produce in a year, but we use up "intermediate consumption" in the process, which leaves us with "net output" which his just about the same as "GDP". That's four different data series right there.

To those four I want to add my context variable "GDS", gross domestic spending. That gives us five series to look at on one graph. You with me? Usually if I have more than two lines on a graph I start to lose clarity. This time it's five. But we're only looking at their relative sizes. That's straightforward.

The source for this graph is the same file as the

Shares of Gross Output graph above. It's on the next tab to the right, so you can look at the numbers if you want. Here's the picture:

|

| Graph #2 |

The

blue line is U.S. Gross Output -- the measure of what we produce in a year.

The

red line is intermediate consumption -- the measure of output consumed in the process of producing output. It is almost half Gross Output. The red is almost half the blue.

The

green line is output left over after using up output (red) to produce output (blue). The green line is just a little over half the blue. The red line is just a little under half; the green is just a little over.

The

gold line is GDP. It is approximately equal to the green. The gold line, we call it "gross domestic product", but really it is the part of output left over after using output to produce output. Almost the same as the green line. It differs for reasons you can read

at Wikipedia.

The

brown line is Gross Domestic Spending. It is GDP plus the business spending that is written off as tax deductions in the process of producing output.

Data sources for Graph #2 --

Blue, Red, Green: UNSNA via UNdata.

Gold: FRED.

Brown: Arthurian.

.JPG)