https://www.reddit.com/r/Economics/comments/7j5pv9/household_debt_recent_developments_and_challenges/

https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1712f.pdf

Household debt: recent developments and challenges (PDF) by Anna Zabai of BIS. From the abstract:

Financial institutions can suffer balance sheet distress from both direct and indirect exposure to the household sector... In a high-debt economy, interest rate hikes could be more contractionary than cuts are expansionary.

The second part of that excerpt is interesting: asymmetry in monetary policy. Also, by implication, in a low-debt economy interest rate hikes could be

less contractionary than cuts are expansionary. This could perhaps mean that there is a middle ground where hikes and cuts are symmetrical. In other words, a Laffer curve for debt and growth,

again.

The first part of the excerpt exposes the paper's focus on

household debt. This is myopia. In our most recent crisis, household debt was the problem (let's say). Therefore, household debt is always and everywhere the problem, and is the only private-sector debt problem worthy of discussion.

No.

Debt lets households smooth shocks and invest in high-return assets such as housing or education, raising average consumption over their lifetimes. However, high household debt can make the economy more vulnerable to disruptions, potentially harming growth.

Here's the thing: The cost of debt is potentially harmful to growth. Therefore, debt is potentially harmful to growth. Therefore, household debt is potentially harmful to growth. I don't have a problem with saying household debt is potentially harmful to growth. But I have a serious problem with a failure to say that

not only household debt is potentially harmful to growth. And it should be obvious that the problem is cost. But it doesn't seem to be obvious -- and not only in this BIS paper.

In order to assess the implications of elevated household debt levels, it is crucial to have a sense of whether households can bear the resulting debt burdens without resorting to large adjustments in consumption should circumstances worsen.

Good sentence.

One might add that the implications of elevated business debt levels can be assessed by its effect on the cost of value added, and probably on the price of traded shares of stock.

One might add also that the implications of elevated financial business debt can be assessed by the risk of onset of financial crisis.

One might add a word on public debt also. Because public debt has a cost, too. However, public debt growth (at least since Keynes) is generally a response to problems arising from private debt. The notion that the economy can be improved by reducing public debt (while ignoring private debt) is most foolish.

If all the noise about the Federal debt was redirected to the concept of reducing the need for Federal debt by reducing the amount of private debt, our economic problems could be solved in a matter of minutes.

Aggregate Demand & Irony:

From an aggregate demand perspective, the distribution of debt across households can amplify any drop in consumption. Notable examples include high debt concentration among households with limited access to credit...

Without limited access to credit, the high debt concentration would get even higher. Therefore, increasing access to credit is not a solution to this problem. Unfortunately, increasing access to credit is a standard tool of policy. That's what got us in trouble in the first place. Isn't it obvious?

Pure Irony:

Monetary policy is likely to have asymmetrical effects in a high-debt economy, meaning that interest rate hikes cause aggregate expenditure to contract more than cuts would cause it to expand (Sufi (2015)). This is because credit-constrained borrowers cut consumption a lot in response to interest rate hikes, as their debt service burdens increase. However, they do not expand it as much in response to cuts of equal magnitude. They prefer to save an important fraction of their gains so as to avoid being credit-constrained again in the future...

(Bold added. Irony in the original.)

A little something for the supply side guys:

From an aggregate supply perspective, an economy’s ability to adjust via labour reallocation across different regions can weaken if household leverage grows over time.

Here ya go:

A growing body of evidence points to the existence of a “boom and bust” pattern in the relationship between household debt and GDP growth (Mian et al (2017), Lombardi et al (2017), IMF (2017)). An increase in credit predicts higher growth in the near term but lower growth in the medium term.

Of course! And regarding the second sentence there, note that "An increase in credit" is an

addition to debt. The reason you get "higher growth in the near term" is that the increase in credit translates into extra spending (in the near term). The reason you get "lower growth in the medium term" is that the extra spending has dissipated by then, and you're just left with the extra cost of the additional debt. Isn't it obvious?

This boom-bust pattern appears to be robust across different samples. Table 2, following Mian et al (2017), takes a first stab at exploring the relationship between household debt and GDP growth by looking at correlations.

A

first stab? Maybe it isn't obvious.

The first row confirms the existence of a boom-bust pattern. Higher debt boosts growth in the near term but reduces it over a longer horizon.

Is it obvious now?

Elevated levels of household debt could pose a threat to financial stability, defined here as distress among financial institutions.

Just a reminder: Our

recent crisis was related to household debt (let us assume). But that does not mean that other private sector debt is not also a problem.

Their thought continues:

In most jurisdictions, this is chiefly because of sizeable bank exposures. These exposures relate not only to direct and indirect credit risks, but also to funding risks.

The problem arises, in other words, not only from the risk of household defaults, but also from problems with the banks' own funding. So you can blame the households for borrowing too much. But you must blame the lenders for putting themselves at risk. And you must blame policy, for putting our economy at risk.

Irony, again:

Financial stability may also be threatened by funding risks (Table 1, column 7). In Sweden (as in much of the euro area), banks fund mortgages by issuing covered bonds, which are held primarily by Swedish insurance companies and other banks. This network of counterparty relationships could become a channel for the transmission of stress, as any decline in the value of one bank’s cover pool could rapidly affect that of all the others.

So it goes.

Okay. We finally get to private debt other than household:

This discussion suggests that household-based credit measures could be good predictors of systemic banking distress, much like broader credit measures (eg Borio and Lowe (2002), Drehmann and Juselius (2014), Jordà et al (2016)).

Borio. Borio is my buddy. (I don't think he knows it, though.)

The next sentences are worth repeating:

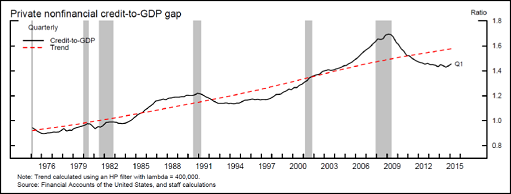

Among these [credit measures], the credit gap – defined as the difference between total credit to GDP and its long-term backward-looking trend – and the total DSR are of special interest. While the credit gap is typically found to be the best leading indicator of distress at long horizons (eg Borio and Drehmann (2009), Detken et al (2014)), the total DSR provides a more accurate early warning signal closer to the occurrence of a crisis (Drehmann and Juselius (2014)). Going forward, establishing the predictive performance of an appropriately defined “household credit gap” and of the household DSR seems especially relevant.

The "credit gap" is an interesting concept. Expect to see more on that, on this blog.

The conclusion of the paper is not satisfying. Well, I take that back. This part is interesting:

Monetary policy could have asymmetrical effects in an economy with high levels of household debt, meaning that an interest rate hike would be more contractionary than an equally sized rate cut would be expansionary.

I missed it before: To get equal up- and down-effects from changes in rates, you need smaller rate hikes and bigger rate cuts. What they are saying is that

high levels of debt push interest rates down. High debt levels may also reduce the "natural" rate of interest, if there is such a thing.

That's interesting.

The rest of the conclusion, maybe not so much:

Central banks and other authorities need to monitor developments in household debt...

Macroprudential instruments such as loan-to-value caps (on the borrower side) or credit growth caps (on the lender side) are designed to force borrowers and lenders to internalise the impact of large credit expansions on the probability of a systemic crisis, thereby aligning private and social incentives. If these measures do succeed in stemming household credit growth, thus containing debt levels, they would also afford central banks greater future room for manoeuvre in setting monetary policy.

With apologies to Anna Zabai: Too intent a focus on

household debt. Not enough concern with the "broader credit measures". I understand that the paper is specifically about household debt. And if the lessons learned here are woven into a tapestry of concern for debt in general, there is much of value here. But please don't forget about the rest of the debt.

Please don't forget about the rest of the debt.