Revised from mine of 21 November 2011, with updated graphs.

As evidence that "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon", Milton Friedman offered graphs showing similarity between the level of prices and the ratio of money to output. But his output number had inflation stripped away, which made his money/output ratio top heavy with inflation. Being top heavy made the ratio look like the path of prices on his graphs. This was Milton Friedman's evidence.

In the real world, you can't strip rising prices from output. In the real world, when prices go up we're stuck paying higher prices. And in the real world, the money/output ratio looks nothing like the level of prices.

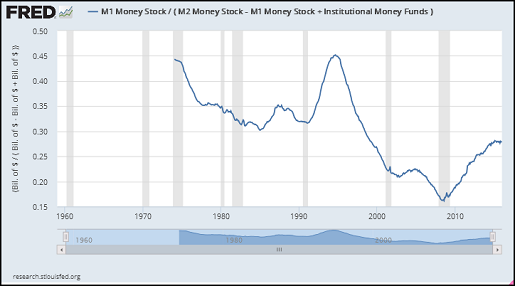

In Milton Friedman's world, the ratio always went up. In the real world, between 1946 and 1981, the ratio went down:

|

| Graph #1, Showing the Money Available to Purchase the Output We Produce |

Milton Friedman's graphs figure output at prices that never go up. His graphs seem to show that there was too much money to buy the output at those fantastic unchanging prices. My graph #1 shows that between 1946 and 1981 we had less and less money with which to pay the prices that were actually charged for the goods and services we call "output".

We had more than 45 cents of spending-money for each dollar's worth of output in 1946. We had less than 15 cents for each dollar's worth of output in 1981.

I added inflation to the graph. The rate of inflation. To look for similarity, I scaled and shifted the CPI data: I multiplied by a number that made the height difference of the CPI about the same as the height difference of the money/output ratio, and then added a constant to slide the whole set of CPI numbers up and get them close to the M1/GDP numbers. My goal was to make the two lines close. I got them pretty close, on the left half of the graph. Not so close on the right half:

|

| Graph #2: Spending-Money per Dollar of GDP (blue) and Inflation (red) |

Look at the left half of Graph #2. Look at the inflationary peaks in the red line. Apart from the inflation of World War One, the peaks pretty well fall within the limit set by the blue line. As the blue line rises, the red inflation peaks also rise, to a high point just at the end of World War II. And after the war when the blue line falls, so also do the peaks of inflation.

But then on the right half of the graph, the lines don't match at all. Inflation flares up again and again in the 1960s and 1970s while the blue money/output ratio continues to fall. Inflation subsides in the 1980s and 1990s, after the blue line has stopped falling.

Inflation moderated when they

stopped tightening money. Isn't that odd?

In the years after 1960 there is no similarity between inflation and the money-to-output ratio.

Before 1960, inflation rose and fell within the limits set by the ratio. But U.S. anti-inflation policy quit working around 1960. Since 1960, the relation between M1/GDP and inflation has been absent.

This failure, this loss of trend similarity on the graph, had a counterpart in the real world. The so-called "Great Inflation" occurred while the money/output ratio showed tightening in the 1960s and 1970s. Then, when the money/output ratio stopped getting tighter, inflation subsided.

This is evidence of an astonishing loss of policy effectiveness.

Why did inflation policy stop working? What caused the loss of trend similarity?

What changed? Our reliance on credit increased. To fight inflation, the Fed suppressed spending-money. To stimulate growth, Congress encouraged credit use. They suppressed the money and encouraged credit use, and our reliance on credit increased.

What changed? Policy suppressed the quantity of money. Policy encouraged the use of credit. We found ourselves using less money and more credit because of policy.

What changed? The thing we use for money changed. We started using credit for money.

The difference between money and credit is that credit is more costly than money. An economy that shifts from low reliance on credit to high reliance on credit finds itself with financial costs rising relative to other costs. It finds itself with interest costs rising relative to wages and profits. It finds itself with living standards squeezed and business growth below par. It finds that finance has become its growth industry.

An economy that shifts from a low reliance on credit to a high reliance on credit will see rising costs that are associated with the cost of interest. Costs that affect prices, associated with the cost of interest.

I added Moody's AAA Interest Rate to the graph, in green:

|

| Graph #3: M1/GDP (blue), Inflation (red), Interest Rate (green) |

I made the red and green lines similar by scaling the green line and shifting it up a bit. After 1960, the green and red are a very good match: Inflation and interest rates show similar patterns. Before 1960, there is little similarity.

Before 1960 blue and red show similarity. After 1960 green and red show similarity. Before 1960, money was our primary medium of exchange. After 1960, credit was our primary medium of exchange.

Before the early 1960s there was too much money in the economy (and not enough credit use). After the early 1960s there was too much credit use (and not enough money).

The early 1960s are the sweet spot.

This is policy guidance.

The early 1960s are the sweet spot.

Preview and download the Excel file containing the graphs and data

//////////////////

UPDATE 19 Feb 2016

I put this post on Reddit in

r/Economics

IslandEcon reposted it to

r/badeconomics

Some discussion there. Useful.

In response to IslandEcon's five points ("The author seems puzzled")

I'd say that I interpret the facts differently than he does.

The ending of the "accord" in 1951 is not observable on my graphs. (so, I think it is not as significant as he says)

And IslandEcon seems to hold velocity in higher regard than its components -- NGDP and the Money Supply. I don't.