At

Rortybomb, JW Mason examines the idea "that the root cause of the crisis is that interest rates were too low for too long."

Mason quotes John Taylor, who says the Fed "held interest rates too low for too long and thereby encouraged excessive risk-taking and the housing boom."

Mason quotes Thomas Hoenig of the Fed:

We as a nation have consumed more than we produced now for well over a decade. Having very low rates for an extended period of time encourages us to continue focusing on consumption, but to correct our imbalances, we have to focus on production. If I thought zero rates would bring jobs, I’d want it forever. But it distorts the economy. In 2003, when we lowered rates and kept them there because unemployment was 6.5 percent — look at the consequences.

Mason writes:

More broadly, this view is associated with so-called Austrian Business cycle theory, which holds that macroeconomic instability is fundamentally due to departures of the market interest rate from the natural rate... In this view, an artificially low interest rate encourages investment in assets whose returns are lower than the true social rate of discount; when interest rates return to their natural level, investment will be depressed until this excess stock of physical capital is worked off.

That's just the opening part of the post, a concept laid out so it can be evaluated. I didn't get to Mason's evaluation yet. I have to work through the introductories.

It is an easy thing to tell a story and end it with the terrible problems of recent years. That doesn't mean there is any relation between the story and the terrible problems. But it can

seem there is this relation, because stories end with conclusions.

John Taylor's story "encouraged excessive risk-taking and the housing boom".

Hoenig's story is "we lowered rates and ... look at the consequences."

Not part of Mason's introductory material, Paul Krugman's story is that we cannot lower interest rates enough because they're already at the lower bound and ... look at the consequences.

I'm not siding with Krugman here. I'm just pointing out that the outcome is always the same. The outcome is always that our problems, the things we don't like in the economy today, are explained by the storyteller's story. The stories always explain the problems. Even when the stories are opposites.

Well, you'd have to expect that, wouldn't you? I do the same thing, I suppose. The goal of the storytellers is to explain the problems.

Still, some stories are better than others. Some stories are thin.

"Look at the consequences" is thin.

"The results we have are due to the factors I describe" is thin.

Let's take them in order. For John Taylor, low rates led to excessive risk-taking and the housing boom. Low rates for too long.

Sure, there is a parallel of some kind between excessive duration and excessive results. (The parallel is in sentence construction and thematic echoing.) And low rates do encourage borrowing and spending and economic activity in general -- or at least we think they do. But Taylor makes it sound like "risk-taking" is a bad thing, though it is the basis of the entrepreneurial spirit. And Taylor relies on results when he says low interest rates led to the housing boom.

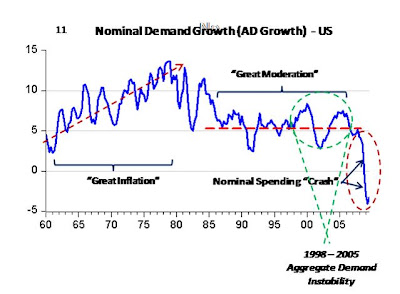

Specifically, Taylor seems not to address the reason the "macroeconomic miracle" of

1995-2000 devolved into the "housing boom" of

1998-2005. Granted, Mason's excerpt leaves out most of what Taylor said. And granted, Taylor would have jacked up interest rates sooner and created the slump in housing sooner. And brought on the crisis sooner, I suppose.

The reason the "miracle" devolved into the bubble is simple and should be obvious: Profit must have been better in the bubble. Money goes where money is, and there was money to be made in the housing bubble, more than in a miracle.

Of course, there is the duration thing that Taylor speaks of, excessive duration. But it's easy to see this, in hindsight. Taylor is pointing out the obvious here, the results. He is not showing that he explains those results. He relies on the existence of the results to make his case for him. This is not good science. It is not even good argument.

Now I will say again the Taylor quote from Mason's introduction is very brief. And I've not yet read the source article. But the brass ring here is not to make claims about causes of things. The brass ring is to demonstrate causes. Some stories are thin.

Taylor's solution would have been to jack up interest rates as the "miracle" was turning into the bubble, and create a recession then if need be. Given that the reason for that turning was the profit motive, the question is not

when is the best moment to cripple the economy. The question is

why is productive effort consistently less profitable than speculation?

The answer, of course, has to do not only with the level of interest rates, but also the frequency of application of the rate of interest as a cost in our economy. To speak of interest rates but fail to consider the reliance on credit, is to present an incomplete and largely incorrect argument.

The quote from Thomas Hoenig is longer. I will break it up.

We as a nation have consumed more than we produced now for well over a decade.

Well, sure. Production went to China, and consumption followed. The consumption still counts as what

we do, but the production doesn't. You have to expect this, when a "mature" and mismanaged economy promotes international trade, and a young and vigorous economy takes advantage of it.

The same owners that used to make money here now make money in China. Microsoft, Google, they're all over there. Why is this encouraged?

Having very low rates for an extended period of time encourages us to continue focusing on consumption, but to correct our imbalances, we have to focus on production.

Why does having low interest rates promote consumption but not production? It's nonsense. Business is drawn to low costs. Does Hoenig suggest business would be better in the U.S. if the high cost of borrowing drove business away?

Or maybe Hoenig means we have to consume less and save more, so that money is available for investment. But if there's money to borrow for consumption, then there's money to borrow for investment. And anyway, if consumption was up, aggregate demand was up, and aggregate supply should have been brought up thereby.

We've been focusing on production since Reagan, by the way. Supply side economics, and all that. It has not worked, of course, and the government has felt pressure to do more for the demand side as well because of it, but this does not mean we have not focused on production. What it means is, the focus on production has failed.

If I thought zero rates would bring jobs, I’d want it forever. But it distorts the economy.

Zero interest rates distorts the economy? This is your concern, Hoenig? Look at the Fed Funds rate:

|

| Graph #1: Federal Funds rate (blue) and 7-year Moving Average (red) |

What goes up must come down. The bigger they are, the harder they fall. Look at the trend since 1981, Hoenig, and tell me you couldn't see zero rates coming. We gave supply-side economics thirty years, and it gave us the Great Recession.

In 2003, when we lowered rates and kept them there because unemployment was 6.5 percent — look at the consequences.

There you go again, Hoenig. The results we got are not evidence that your version of the story is right.