I'm gonna use base money as a measure of the money the Federal Reserve puts into the economy. I'm gonna use the Federal debt as a measure of the money the U.S. Treasury puts into the economy. And I'm gonna use FRED's TCMDO -- with the Federal government's share subtracted out of it -- as a measure of the money that everybody else puts into the economy.

(If that doesn't seem right to you let me know -- but be specific about the data I should use and where I can find it -- and I will do the graph over using your data.)

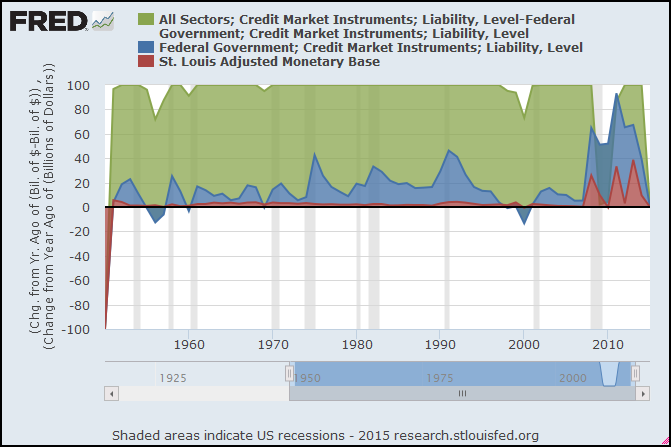

I'm going to look at the annual changes in these money measures (change in billions, not percent change).

I'm using Federal debt held by the public rather than "gross" Federal debt because the difference is borrowed from money that was already in the economy.

Here's a first look:

|

| Graph #1: A Stacked Area Graph showing Percent of Total (I duplicated the graph at FRED to get the link;) |

The green area represents money borrowed in the private sector and spent into the economy. So I guess we can see who it is that has been putting inflationary amounts of money into the economy. I guess we can see who it was, in the years leading up to the 1965 debasement of U.S. silver coin, we can see who it was that generated the inflation that finally forced the hand of government, forcing the debasement.

It wasn't the Federal government that did the forcing. It was the private sector. The inflation that forced the debasement of U.S. coinage was due primarily to private sector credit expansion, not to the government printing money. Thus we are justified, saying that debasement occurred because the government's hand was forced. This forcing of government's hand by private sector credit expansion, this is a recurring problem. This is the problem that topples nations.

This is the problem that must be addressed.

17 comments:

I'm not sure what I'm looking at in your graph.

What is the green line? I was guessing YoY % change, but that's nowhere near the 100 line that you have.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=1aas

Just trying to understand.

Cheers!

JzB

Jazz-

As the broadest measure of private sector money supply growth, its interesting to add CPI to that graph see how the private money supply growth rate changes reflect changes in CPI. And furthermore, just how much of an outlier the 70's inflation was relative to the rest of the last 60 years. I wonder what else may have happened to influence those high inflation levels? (Hint: add oil price and the answer is clear).

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?graph_id=237295

And its interesting also to add GDP and notice how close the correlation is.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?graph_id=237296

Looks like to me that if you want to have high real GDP growth and low private sector credit growth, then we would need a significant increase in spending from either the government or foreign sector.

Hi Jazz. Yeah, I don't have full confidence in that graph, myself. It is a stacked area graph, so the three components should stack up to 100% of the total. They do, except where something goes negative; I guess that makes sense. And then there is that big hole during the crisis...

The graph does not show percent change from year ago, as yours does. Here was my thought: I want to add up all the money that gets added into the economy each year (in billions) and compare Fed billions to Treasury billions to nonFederal billions.

FRED's vertical axis label tells a lie when you make a stacked area graph. The graph shows each component as a percent of the total of the three components. The vertical axis goes up to 100 because it is showing percent. But the vertical axis label doesn't tell you what I'm telling you.

For a comparable erroneous vertical axis label, see

http://onthedeathoffred.blogspot.com/2015/01/christian-zimmermann-has-bad-day.html

Hi Auburn

"Looks like to me that if you want to have high real GDP growth and low private sector credit growth, then we would need a significant increase in spending from either the government or foreign sector."

Yes. Or perhaps reduce the rate of flow into savings, so that people are left with more money to spend.

You saw what happened with quantitative easing. Most of that significant increase ended up as excess reserves, a form of savings.

Auburn -

I'm not sure you want high RGDP growth. I think you want some healthy, sustainable RGDP growth. If it's a tad above population growth, then you can have a general increase in standard of living, if distribution is equitable.

Our balance of payments is unfavorable, so gov't spending is still probably the answer. Instead, we have austerity.

Art -

I didn't know you could do stacked graphs a FRED. As your death of fred link shows, things get screwy.

Cheers!

JzB

Art-

Govt IOUs are self-contained within the Govt's balance sheet. QE swaps one type of Govt liability for another but does not and cannot add to Govt liabilities. Which is to say that QE does not and cannot change the level of non-govt savings, it can only change the asset composition. There is literally nowhere for those reserves to go in the aggregate except into TSY security accounts on the Govt's balance sheet as Govt IOUs are a closed system (excluding the level of physical cash which is pretty much constant).

Only fiscal policy can change the size of the non-Govt's net financial position.

Auburn, what are you responding to?

Art-

"Yes. Or perhaps reduce the rate of flow into savings, so that people are left with more money to spend.

You saw what happened with quantitative easing. Most of that significant increase ended up as excess reserves, a form of savings."

QE didnt increase anything. The TSY securities were private sector savings just like excess reserves are.

"QE didnt increase anything."

Well Auburn, if you look at the rightmost inch of the graph, the red line shows three quite obvious increases. So I think QE pretty clearly did increase something.

So maybe there was change only in "asset composition", a decrease in treasuries offsetting the increase in base money or whatever. Whatever.

I used QE as an example of an increase in savings. It was an afterthought, to provide the example, that's all.

Don't focus on the example. Focus on the level of savings.

The point I was making was that in order to have "high real GDP growth and low private sector credit growth" (your words), then as an alternative to "a significant increase in spending from either the government or foreign sector" (your words) we might be able to achieve that objective by reducing "the rate of flow into savings, so that people are left with more money to spend" (my words).

It doesn't bother me that I'm wrong sometimes. I'm wrong a lot. What bothers me is that you choose to ignore the interesting idea I put forward, and to focus instead on the bad example.

Art wrote: we might be able to achieve that objective by reducing "the rate of flow into savings, so that people are left with more money to spend"

That puzzled me when you first said it. Now that you said it twice I have to ask.

How are you planning to change the world so that statement makes any sense?

It's my understanding that people who save are "left with more money to spend" and people, who save not at all, are left with no money to spend.

Minsky would say that in the 50's and 60's we had such a world as you would like. Back then people believed in Social Security and they felt that a job with health care benefits was a given. Today people no longer believe and that motivates them to want to save more so that they don't end up left with no money to spend.

Art-

""QE didnt increase anything."

Well Auburn, if you look at the rightmost inch of the graph, the red line shows three quite obvious increases. So I think QE pretty clearly did increase something."

Yes, money in reserve accounts was increased and money in securities savings accounts was decreased. The private sector exchanged checking deposits for savings deposits. So the financial position of the private sector is unchanged by QE.

"So maybe there was change only in "asset composition", a decrease in treasuries offsetting the increase in base money or whatever. Whatever."

Its not "whatever" misunderstanding QE and the fiscal\monetary operations has led to immense damage. QE is widely viewed as "money printing" when in fact it is nothing of the sort. When private banks swap their customers deposits out of CD accounts and into checking accounts, nobody on earth would consider this "money printing" but for some reason, when the Govt bank does the exact same thing, its suppposed to be stimulative?

"I used QE as an example of an increase in savings. It was an afterthought, to provide the example, that's all."

Just pointing out that the example is wrong, thats all.

"Don't focus on the example. Focus on the level of savings.""

The level of private sector net savings can only be increased via Govt deficits or a change in the trade balance.

"The point I was making was that in order to have "high real GDP growth and low private sector credit growth" (your words), then as an alternative to "a significant increase in spending from either the government or foreign sector" (your words) we might be able to achieve that objective by reducing "the rate of flow into savings, so that people are left with more money to spend" (my words)."

Yes, if we were to lower income inequality, which is to say, more money in the hands of people with a higher propensity to spend, then we would get higher spending and growth, this is exactly how things worked during the golden age of capitalism in the 40's, 50's, & 60's.

What policy is easier to implement?

Punishing the 1% (from their POV) via increased taxes and then increasing spending on the 99%. Which the 1% will fight tooth and nail

or

Simply spending the money on the 99% without punishing the 1%?

Seems to me that the 2nd approach would be easier to implement

"It doesn't bother me that I'm wrong sometimes. I'm wrong a lot. What bothers me is that you choose to ignore the interesting idea I put forward, and to focus instead on the bad example."

I didn't mean to ignore the second part, I just didnt have anything meaningful to contribute at the time. I was simply offering up a correction on what is a widely misunderstood and extremely improtant issue (the effects of QE).

Jim: "It's my understanding that people who save are 'left with more money to spend' and people, who save not at all, are left with no money to spend.

Minsky would say that in the 50's and 60's we had such a world as you would like. Back then people believed in Social Security and they felt that a job with health care benefits was a given. Today people no longer believe and that motivates them to want to save more so that they don't end up left with no money to spend."

Well, people who save are left with more money, period. Not necessarily more money to spend.

Jim, you are looking at the situation like one of the "Today people" you mention.

The more people cut back spending to increase their savings, the more the people they used to pay are forced to cut back their own spending, and so on in a downward spiral known as the Paradox of Thrift. Income shrinks so fast that savings fall instead of rise. The result: mass unemployment.

Excessive saving, which Keynes deemed to be anything beyond money needed for predictable needs like retirement or education, was a serious problem for the economy, and would likely result in recession or even depression. Saving means people are not spending, and when there’s not enough spending going on, the economy declines.

Jim, you seem to think the way this guy thinks: It is not that people never spend, only that they decide to save now to spend it at a future date.

That's very nice. But it's not very specific. Anyway, as you say, people want to save more in that future when the economy goes bad. The irony is that it's too much saving that makes the economy go bad in the first place. Oh, and by the way, this is that future.

Jim, the view you express is that people only have money to spend if they don't spend it, and people that spend it all don't have any. But money that is spent ends up in the hands of other people; and that is true just as long as people keep spending it.

Keynes bemoaned the maxims which are best calculated to "enrich" an individual by enabling him to pile up claims to enjoyment which he does not intend to exercise at any definite time. You can't just assume that savers will spend in the nick of time to avoid calamity. As you say: when calamity comes, even the spenders save. Things get worse.

Things get worse because we think it wise to find ways to "enrich" people by enabling them to pile up claims to enjoyment without them ever intending to enjoy those claims.

Auburn:"When private banks swap their customers deposits out of CD accounts and into checking accounts, nobody on earth would consider this "money printing" ..."

When deposits move from CDs to checking accounts, M1 money is certainly increased.

If you want to insist that's not "printing", that's probably just a matter of definitions.

Lets suppose we all agree that savings drags down the economy.

AuburnP is arguing the MMT line. According to MMT, savings (spending less than income) is a demand leakage that can be offset by Federal borrowing (printing and selling Treasury Securities). As long as the govt reduces taxes or increases spending large enough to cover savings, people can save as much as they want.

You apparently don't like that solution.

So what is your solution?

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is made more difficult by the fact that people will likely double-down on their effort to save if they begin to suspect the govt is trying to prevent them from saving.

Art-

"When deposits move from CDs to checking accounts, M1 money is certainly increased.

If you want to insist that's not "printing", that's probably just a matter of definitions."

The only universe in which the $10K I have in a 6-mo CD at Chase is not considered "money" and so when it matures in June I all of a sudden have $10K in new "money" is a parallel universe that is stranger than I can imagine.

Definitions matter, which is why if you fail to include term deposit savings accounts in your analysis of the "money supply" you will come up with wrong conclusions and policy suggestions.

Garbage in....Garbage out

Jim-

"AuburnP is arguing the MMT line. According to MMT, savings (spending less than income) is a demand leakage that can be offset by Federal borrowing (printing and selling Treasury Securities)."

Almost exactly right Jim. I would just add that "savings is a demand leakage" is not an MMT POV, its a simple accounting observation. Nothing subjective about this statement. And issuing TSY securities is not "borrowing" in any conventional sense. The US Govt never has to deliver any financial assets to pay off its supposed "borrowing". Whereas you and I must deliver financial assets to pay off our mortgages and credit cards, the Federal Govt "pays off" one type of its financial liability (securities) with another type of its financial liability (reserves).

This is a fundamentally different concept.

"As long as the govt reduces taxes or increases spending large enough to cover savings, people can save as much as they want."

This is well said. Just remember that the trade deficit is foreigners "saving" dollars so the Govt needs to offset that as well.

"Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is made more difficult by the fact that people will likely double-down on their effort to save if they begin to suspect the govt is trying to prevent them from saving."

Another interesting dynamic to think about is the effects of reducing social insurance programs. If the Govt announces cuts to SS in order to "save money to pay for future SS payments" then the private sector will be forced to save even more money for its retirement. So not only do we get the first order effect from SS cuts that the recipients would have less spending power right now, everyone else will also be forced to spend less in order to save more for their future financial security.

Now, contrast SS cuts with a program to expand SS significantly to every man and woman over 65, maybe something on the order of 2X the poverty level income for an indiviudal per month, something like $2500 a month. Think about how much money public would free up to spend would if they didnt have to save so much for their retirements. I know that a guaranteed financial standard of living would drastically alter the way in which I manage my balance sheet.

Post a Comment