"How to get out of debt in '10"

That's the page-one teaser in my local paper: Get out of debt. Story, page 32.

From page 32:

Challenging the Premisses

| Start with the debt problem, three views of it,

and the most important thing. Here's a longer look at the debt problem.

Here's a short one on economic policy, some surprising trends, and a few unusual policy recommendations. How'd we get into this mess? Read Policy Venn and Policies of the Venn Overlap. Still with me? Read A Matter of Life and Death. And for an overview, download my 12-page PDF |

| "Good Money" | "Bad Money" |

|---|---|

| Not Debased | Debased |

| Heavier | Lighter |

| More Valuable | Less Valuable |

| More Expense | Less Expense |

| More Costly | Cheaper |

Gresham's law is commonly stated: "Bad money drives out good", but more accurately stated: "Bad money drives out good under legal tender laws".

| Slow going for stimulus funds BY CHRIS MCKENNA As construction grinds to a halt for the winter, less than 40 percent of the $47.1 million in federal stimulus money budgeted for road, bridge and sidewalk improvements [in the region] has trudged through bureaucratic obstacles to the contract stage, state Department of Transportation figures show. And only about 10 percent of the money has made it into the economy so far as incremental reimbursements to the contractors who are doing the work.... How many jobs the local road-and-bridge work has saved or created is impossible to say. |

| What I said. |

The power of economic growth was driven home to me by a study that suggested that a 1 percent increase in our economic growth rate would shrink the federal deficit by $640 billion over the next seven years, would increase federal tax revenues by $716 billion without a tax increase, and that each and every adult citizen would earn $9,600 more than they would in the current growth projection.

In this world of merely 1 percent higher growth, the Social Security Trust Fund never runs out of money....

Thanks for the update, Kevin.

"Unfortunately, macroeconomics has been in utter disarray since the Keynesian consensus broke down in the 1970s."

"Keynesianism was the economics of the world from around 1940 through the 1970s, but in the 1960s and 1970s came this extraordinary and quite unexpected inflation. And that took the bloom off the [Keynesian] rose. The Keynesian schema, which had tremendously wide acceptance, had no theory of inflation.... Since then, no new view that anyone can agree on has emerged, and there has been a vacuum in terms of a defining picture of what the hell economics is.... In the history of economic thought there has never been such a prolonged period of intellectual disagreement."

So in my view you can only expect to see agreement on what tight money means when there is agreement on the appropriate model. That seems to be much farther away than it was in the 1970s when students could look at papers by Tobin and Friedman and say, what’s the argument about, the length and variability of lags, is that all? Fine tuning bad, coarse tuning good. There was a mainstream then, with only Austrians and Post-Keynesians and suchlike outside it. There is no mainstream now....

Following the Secret Economist's Altig link brought me to this:

"It is fair to say, however, that the core macroeconomic modeling framework used at the Federal Reserve and other central banks around the world has included, at best, only a limited role for the balance sheets of households and firms, credit provision, and financial intermediation. The features suggested by the literature on the role of credit in the transmission of policy have not yet become prominent ingredients in models used at central banks or in much academic research."I will admit that economists were not exactly ahead of the curve with this agenda, but prior to 2007 it was not at all clear that detailed descriptions of how funds moved from lenders to borrowers or how short-term interest rates are transmitted to longer-term interest rates and capital accumulation decisions were crucial to getting monetary policy right.

If you look up "Taylor Rule" in Wikipedia, this is what ya get:

There's more, but I got scared off by that big, ugly formula.

Well check it out! it also says this:

This is totally amazing. The inflation problem is solved. The unemployment problem is solved. Plus, problems I don't even know about: The uncertainty problem is solved. And the credibility problem is solved.

The only problem that remains? Idiots. Either the people that use the Taylor rule, or the ones who posted that joke, or me for not getting it. Pro'bly me.

The name Anna Schwartz should ring a bell. She wrote a very great book (which I never read) with Milton Friedman, who was a very great man. Schwartz has some thoughts on the money supply, here. I have just a few remarks.

The Secret Economist recently posted an evaluation of the Taylor rule.

What's the Taylor rule? According to the Wik, the Taylor rule "stipulates how much the central bank ... should change the nominal interest rate" when inflation and economic growth wander from their targets.

Long story short, the Secret Economist became "suspicious" of the good match between the Taylor numbers and the "Federal Funds" interest rate, and decided to investigate. The bold conclusion: "The Taylor rule fits because it is an identity."

Now, Wikipedia says, "An identity is an equality that remains true regardless of the values of any variables that appear within it." So SE's conclusion is that the Taylor calculation will always give a good match to the interest rate. Suspicions justified.

But -- as Arlo Guthrie said -- that's not what I came to tell you about.

. But we know that

. But we know that  is a fraction, and that

is a fraction, and that  . In order to understand our calculation, we can replace the

. In order to understand our calculation, we can replace the  in the calculation with the thing it equals, thus:

in the calculation with the thing it equals, thus:  . It is evident now that in our calculation, we are dividing by a fraction.

. It is evident now that in our calculation, we are dividing by a fraction. gives us

gives us  . Now, multiply

. Now, multiply  by the inverted fraction:

by the inverted fraction:  .

. , and to rearrange terms:

, and to rearrange terms:  . We can add parentheses to show we do the division first:

. We can add parentheses to show we do the division first:  . All of this is valid arithmetic.

. All of this is valid arithmetic. will produce the same result as

will produce the same result as  , our original calculation.

, our original calculation.

is the quantity of money.

is the quantity of money. is real output.

is real output. is output in actual prices.

is output in actual prices. is the price level (the "deflator").

is the price level (the "deflator").

"The goal of GDP is to summarize in a single number the dollar value of economic activity in a given period of time."

"Models have two kinds of variables: endogenous variables and exogenous variables."Ooh, I need this. I don't know these big words. I'm interested in the economics, but the big words are a problem for someone of little memory. (The big words are so troubling that I don't even notice Mankiw uses the word variables three times in that sentence.)

"Endogenous variables are those variables that a model tries to explain. Exogenous variables are those variables that a model takes as given. The purpose of a model is to show how the exogenous variables affect the endogenous variables."Okay this is good. I'm looking at it like computer programming. Send some values to a function, and get a return value. The values I send are exogenous. The return value (calculated by the function, based on the values I send) is endogenous. I get it.

"In other words, as Figure 1-4 illustrates, exogenous variables come from outside the model and serve as the model's input, whereas endogenous variables are determined inside the model and are the model's output."Just like a function in C. Arguments come from outside the function and serve as the function's input, while return values are determined inside the function and are the function's output. Okay.... (Arguments, or parameters maybe. I'm not always clear on the big words.)

...one thing that’s hard to convey is how boring business seemed in the 1960s and 1970s. (”I’ve got just one word for you: plastics.”)

But even a decade later, it was the guys who went off to investment banks who were buying the third homes.... And it wasn’t just the money: business stopped being so boring, and was even getting to be fun for some people.

From PK's post of 7 October 09:

Everyone agrees that this is a stopgap, and we want to get the Fed out of the business of private lending over time.

But here’s my question: why does it have to be a return to shadow banking? The banks don’t need to sell securitized debt to make loans — they could start lending out of all those excess reserves they currently hold. Or to put it differently, by the numbers there’s no obvious reason we shouldn’t be seeking a return to traditional banking, with banks making and holding loans, as the way to restart credit markets. Yet the assumption at the Fed seems to be that this isn’t an option — that the only way to go is back to the securitized debt market of the years just before the crisis.

Why? Are we still convinced that securitization is a far superior system to conventional banking, and if so why?

Inquiring minds want to know.

If I said I was getting "positive feedback" you'd probably figure I heard from people who like my posts. If I said "negative feedback" you'd figure they didn't like 'em. Fair enough. That's probably what I'd mean. But y'know, if that was all there was to it, I wouldn't be writing this post.

Tack the word "loop" on to those feedback phrases, and the meanings are totally different. A positive feedback loop is a self-reinforcing loop. A negative feedback loop is self-negating. These are not at all the meanings we ordinarily use. We might think of a bad situation making itself worse as a negative thing. But it's a positive feedback loop.

In yesterday's post, "The true fiscal cost of stimulus," Paul Krugman writes:

So fiscal expansion is good for future growth. Still, it does burden the government with higher debt, requiring higher taxes or some other sacrifice in the future. Or does it? Well, probably — but not nearly as much as generally assumed.

Y'know, I like the guy. I like a lot of what Krugman says. But he's desperately trying to make an argument here in favor of debt. When I read it I was sympathetic, but I don't buy the argument. He's waffling, and he's trying to weasel around the problem of insurmountable debt.

One way the Federal Reserve can fight inflation is to sell some of its assets. If it sells a T-Bill to someone, in exchange the Fed receives money that someone was willing to spend. That money, spending-money, is M1 money. The Fed receives that money and holds it, and it is no longer in circulation. It comes out of M1.

I get it now. A few days ago I wrote You can only either spend or save. I wrote People make their own decisions.

Here's the thing: You can only either spend or save. But while you're deciding between the two, you are holding money.

The heavy line between HOARD and FLOW represents the range of possible attitudes toward holding money. Call it the Hold line. If you don't hold money very long, your spending happens near the FLOW end of the line. If you do hold money a long time, your spending shows up closer to the HOARD end.

The diagram also shows that hoarding is not the same as saving. If you save a dollar, your bank will put it to use, lending out multiple copies of it. But until you put it in the bank, you are holding that dollar. And as long as you hold it, no one is putting it to use. The money you hold may count as being in circulation; but it is not in circulation. Just like at the Fed.

...there springs up among them an extravagant love of gain--get another

man's and save your own, is their principle; and they have dark places

in which they hoard their gold and silver, for the use of their women

and others; they take their pleasures by stealth, like boys who are

running away from their father--the law....

"...a run that results in hoarding of cash by the public tends to reduce the total money supply."

"A hoarder who earns no money interest on his mattress cache finds the real value of his wealth increasing every day as prices fall."

The convenience of paying by check and the credit card revolution would suggest a declining need for currency. But, curiously, the amount of coins and paper money in circulation has increased significantly.

A rising price for silver in the Sixties made the old coins... worth more intrinsically than their face value. Silver coins rapidly disappeared into private hoards...

Tax evasion is believed to be a significant factor in the demand for currency... [People] receive payment in cash so that there is no record. Much of this money ...winds up... in safe deposit boxes, under the mattress, or in fruit jars buried under the old apple tree.

"Many good historians have told us of the shortage of coins in Europe

in the Dark Ages. Coins were scarce; and they were scarce partly

because the supply of precious metals was scarce and partly because a

tremendous and widespread propensity to hoard drained relatively large

amounts of the existing metals from the current supply."[p.9]

"While the transaction demand for coins was very much depressed [in

the Dark Ages], the demand for coins as assets to be hoarded was

exceedingly high. This sort of demand, though, had rather disruptive

effects on the working of the monetary system; it subtracted

continuously coins from business circulation for unreasonable lengths

of time and tended to shift them into the class of jewelry"[p.11]

"Antonine of Florence also notes the influence of supply indirectly,

in his remarks that, when gold is hoarded, it becomes scarce, and more

goods will be given for the same money."[Monroe p.26]

"economies ...stall... for much of human history, in a slough of depression caused by insufficient buying power, stagnant savings, and hoarded funds." [p.33]

"The destruction of the inducement to invest by an excessive liquidity-preference was the outstanding evil, the prime impediment to the growth of wealth, in the ancient & medieval worlds." [p.351]

How are we gonna solve the big problems if we don't even know the meaning of little words?

Milton Friedman used to write about "the amount of money people want to hold." I never quite understood it. I want to hold lots of money. Who would want to hold less? It never made sense to me.

The Wikipedia article "Money Supply" this morning contains this statement:

Since most modern economic systems are regulated by governments through monetary policy, the supply of money is broken down into types of money based on how much of an effect monetary policy can have on each. Narrow measures include those more directly affected by monetary policy, whereas broader measures are less closely related to monetary-policy actions.

For the late 1970s was when macroeconomics experienced its great divide. It’s a period engrained in the memory of those of us who were young economists at the time, trying to find our own paths. Yet I haven’t seen a clear explanation of what went down at the time. So here’s a sketch, which I hope a serious intellectual historian will fill in someday.

Come to think of it, there's not much difference between

1. People finding somebody to blame, like Greenspan or Keynes; and

2. Economists laying the blame on people for being complex.

It's the same blame game.

When my son Aaron was in the first grade, he came home from school one day all upset. I asked him what was wrong. He said, "They told us we have to study. I don't know how to do that."

It wasn't a big problem, really. And he since became an engineer.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia:

Behavioral economics and behavioral finance are closely related fields that have evolved to be a separate branch of economic and financial analysis which applies scientific research on human and social, cognitive and emotional factors to better understand economic decisions by consumers, borrowers, investors, and how they affect market prices, returns and the allocation of resources.

"When economists write textbooks or teach introductory students or lecture to laymen, they happily extol the virtues of two lovely handmaidens of aggregate economic stabilization -- fiscal policy and monetary policy." - Arthur Okun

In 1977 when I got my three credits in economics, I learned that the government had two tools to use for managing the economy: monetary and fiscal policy. Maybe they don't teach this anymore. Maybe that is the problem.

"So here’s what I think economists have to do. First, they have to face up to the inconvenient reality that financial markets fall far short of perfection, that they are subject to extraordinary delusions and the madness of crowds. Second, they have to admit... that Keynesian economics remains the best framework we have for making sense of recessions and depressions. Third, they’ll have to do their best to incorporate the realities of finance into macroeconomics...."

Here it is in shortform:

1. Economists have ignored the imperfection of markets.

2. Keynesian economics provides the best understanding.

3. Economics must incorporate the realities of finance.

Going thru the wormhole and coming out on my side, we get the following:

Suppose you invented a carburetor that gave you 200 miles per gallon. What would you do? Put one on your own car, obviously. Sell them to your neighbors. Or just give them away to get things started. Word-of-mouth. Invent a better mousetrap and people will come knocking at your door.

Suppose you came up with an economic theory that explained a lot. What would you do? How would you install it? How would you show that it works?

If we were on the gold standard, the Forgiveness could not be done. You can't print gold. Fiat money is flexible. Unfortunately, we have not yet learned how to take advantage of the features of fiat money. We know only how to create inflation.

Roosevelt came to office at a desperate time, in the fourth year of a worldwide depression that raised the gravest doubts about the future of Western civilization. "The year 1931 was distinguished from previous years...by one outstanding feature," commented the British historian Arnold Toynbee. "In 1931, men and women all over the world were seriously contemplating and frankly discussing the possibility that the Western system of Society might break down and cease to work." On New Year's Eve 1931 in the United States, an American diplomat noted in his diary, "The last day of a very unhappy year for so many people the world around. Prices at the bottom and failures the rule of the day. A black picture!" And in the summer of 1932 John Maynard Keynes, asked by a journalist, whether there had ever been anything before like the Great Depression, replied: "Yes, it was called the Dark Ages, and it lasted four hundred years."

From: The FDR Years: On Roosevelt and His Legacy By William E. Leuchtenburg

in The Washington Post

What are we waiting for? The fall of Rome?

We're talking ourselves silly. Among the forces that drive the economy I list "human nature." Fickle. For the first couple months after inauguration, President Obama spent much time warning us just how serious was our economic situation. And everything seemed to be getting worse. Then suddenly the talk all turned to "green shoots," and now everything seems to be getting better (at least if you listen to the news). Our whole economic policy now boils down to an audacity of hope.

The economy is driven largely by human nature. Largely, but not entirely. Here's what human nature does for us: It allows us to expect existing conditions to continue. When things are bad, we can see no end in sight. And when the economy is doing well, we can see no end in sight. And when we're in the midst of an unsustainable housing bubble, we expect housing prices to continue upward at least until we've made a killing. Men are fools. That's what drives the economy.

So the Fed is printing dollars by the trillion now. A trillion dollars is a lot of money. How much? It's a thousand billion -- a thousand dollars apiece for a billion people. We don't even have that many people in the USA. Our population is less than a third of that. A trillion dollars is three grand apiece for us, with something left over. It is a lot of money. Twelve thousand dollars for a family of four. For every family of four.

And what is the Federal Reserve doing with all that money? Typically, they do one of two things: Either they lend it to the banks, or they lend it to the government.

So we have a "credit crisis" brought on by excessive debt, and the Fed's solution is to print more money and use it to create even more debt! Is that reasonable? There seems no way to make sense of it. One could say the Fed is too intently focused on its role as "the lender of last resort."

I am still in the midst of my Mises Month, reading and parsing the Mises Daily email and learning about Austrian economics. But today's Daily merits special attention. The article, by Art Carden, rejects the notion of rent control.

Carden says rent control "ignores the information-transmitting function of prices." That got me thinking about how strict the Austrians are regarding free-market principles. But even Austrians fall short, when it comes to taxes.

I'm not a "gold standard" guy. But sometimes it's useful to think in terms of money-as-gold when thinking about the economy. So let's say the U.S. base money is gold. M0 is gold.

Then M1 money is gold in circulation, and I suppose gold certificates, and checking-account money. And after that, M2, M3, whatever, we have "debt-backed obligations." Okay? So let's start up this economic model and let it run.

Recently I've been reading the Mises Daily email.

The Mises Daily expresses the view called Austrian economics. (I subscribed to the Daily to learn a bit about that branch of the subject.) The Austrian school is highly concerned about the possibility of inflation. The school objects to government interference in the economy, favoring Laissez-faire. And, judging by the Daily, they're an opinionated bunch. That's what I've picked up so far.

But then the 7-21-09 post by Thomas J. DiLorenzo caught my eye:

I recently received in the mail the 2008 Annual Report of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. The title of the report is "The Current Economic Crisis: What Should We Learn from the Great Depressions of the 20th Century?"

Now that's my kind of report: reputable source, fascinating topic. So I took a gander at the Fed report. The thing that most struck me was... Well, here's how it opens:

The current financial crisis has prompted these questions: Could the world economy enter a great depression like that of the 1930s? If so, what can governments do to avoid it?

Really??? Now they're gonna think about the possibility of economic depression? Now that it's upon us? Now that all sorts of bizarre policies to skirt depression are being put to the test? What have they been doing for the past 30 years? The fact of the matter is, in observations like this I find an explanation for how things went so terribly wrong: Incompetence, dogma, and ego. But I wander.

The Mises post expresses displeasure with the Fed report: "No mention at all is made of central-bank monetary policy as possibly introducing economic instability...."

Having ignored the role of central banks in generating boom-and-bust cycles, the "lesson" the Minneapolis Fed economists claim to have learned from their study of past depressions is that the "cure" is even more central bank inflation. "[G]overnments need to focus on providing liquidity," they solemnly intone. Following Alan Greenspan, they blame the current depression in the United States on a new version of "the yellow peril": impoverished Asians who have a penchant for saving a large percentage of their income. "Over the past decade, lending by China and other countries in East Asia … has kept world interest rates low." This is what fueled the real-estate boom, they say, ignoring altogether the role of Fed policy, as well as the policy of every arm of the federal government that is involved in housing (from HUD to Congress to the Fed itself) to force mortgage lenders to make bad loans to unqualified borrowers to achieve its goal of "making housing more affordable." (In reality, worldwide savings rates during the 2001–2008 period were actually lower than they were during the previous 15-year period.)

I'm not quoting this for its criticism of government. The quote is important I think because it exposes a topic about which too little has been said: The idea that the Western boom was fueled by the lending of Eastern nations -- the new "yellow peril," DiLorenzo calls it (I assume that wording is his. I think it unlikely Alan Greenspan used the phrase.)

DiLorenzo's observation of the low savings rate in this decade presents an interesting objection to the "yellow peril" view. If global saving is less in the current decade than it was between 1985 and 2000, the notion of excessive Asian saving as a driving force behind recent events does come into question.

On the other hand, it's common knowledge that our Government borrowing has been largely funded by Chinese lending; we worry about that. So it's easy to believe that Eastern lending fueled the Western boom.

I should point out that my post here contains no facts whatsoever. I'm gathering opinion and widespread belief. I'm feeling my way around the edges of a concept.

At present, I have only one other source of information on the "yellow peril" view. That is a review of Martin Wolf's book Fixing Global Finance. (The review is by John Mason.) I've only seen Wolf a few times on TV, but he strikes me as an exceptional mind. (Perhaps because he so often agrees with me.)

In any event, I recognized Wolf's name in the book review and made note of the article, and remembered it now when I needed it (after six months). Here is a relevant excerpt from Mr. Mason's review:

It's also a worthwhile read because of the story Wolf weaves to explain the development of the imbalances in world markets that resulted in the current financial and economic crisis. The author puts forth the “savings glut” theory to describe how the world evolved through the early 2000s. It is important to understand this theory because it is the one that was developed by and acted upon by the current Federal Reserve Chairman, Ben Bernanke. The theory absolves the Federal Reserve actions of the past eight years of blame for the current financial difficulties.

First, note that the "savings glut" theory describes the same trend as DiLorenzo's "new yellow peril:"

The basic idea is this: Emerging economies, like China... began to establish macroeconomic policies along with exchange rate management techniques aimed at fueling export-led balance of trade surpluses.... Savings soared in these countries and the governments started accumulating enormous international reserves. “Two-thirds of all the foreign-currency reserves accumulated since the beginning were piled up within less than seven and a half years of the new millennium.” That is, between December 1999 and March 2007.

Next, note the dates. According to Mason, the new macroeconomic policies observed by the savings-glut theory began emerging during or after 1998 and "evolved through the early 2000s." And the bulk of (Asian) foreign-currency reserves accumulated since those policies were put in place.

Now, if savings and foreign-currency reserves travel in tandem in these emerging economies (as Mason implies) then most of their saving occurred in the current decade. If that is true, then DiLorenzo's observation is irrelevant or false. If DiLorenzo is right and relevant, then Martin Wolf is wrong.

I am disappointed. My technique for learning is to find two sources on a topic and compare them. I figure if the two fit together and make sense, then I understand the topic. In this case, either I misunderstand, or at least one of the sources is junk. It's time to move on.

John Mason (the book reviewer) writes:

I tend to lean more to what Wolf calls the “money glut” theory of the world’s financial imbalances. In this theory, these world imbalances came about from a central bank that underwrote negative real rates of interest and served as a “bubble machine” that helped distort asset markets. Within the context of the bubble, “the credit expansion was associated with what was, in retrospect, unsound lending of a particularly innovative kind...."

Money-glut yes, savings-glut no. My gut reaction is to agree with Mr. Mason on this point. Mr. DiLorenzo seems to feel the same way. So you have on the one hand the weight of Mason and DiLorenzo and me... and on the other Bernanke and Greenspan! For what that's worth.

I checked out Mason's blog to see if he's in the Austrian school. (The view he shares with DiLorenzo has a wider base if they're not of the same school.) Mason looks not to be Austrian. A search of his blog for the word "Austrian" turns up no result.

Our Federal Reserve System establishes a Reserve Requirement for member bank funds. This determines how much each bank must keep in reserve. Since 1990 or so the Reserve Requirement on money in checking has been 10% and on money in savings has been zero. There is more money in savings than in checking in the U.S., so the zero rate predominates. In addition, the thing works like an electrical circuit: Check-money has a resistance of 10 ohms and savings have a resistance of zero, a short-circuit. All the electrons that cannot pass thru the 10-ohm circuit can easily pass thru the short.

Our effective Reserve Requirement is zero.

What does this mean? Well, you divide one dollar by the Reserve Requirement (RR) and that tells you how much money can be created from one dollar under our system of fractional reserve banking. If the RR is 25%, one dollar can become (1/0.25) or $4. If the RR is 10%, one dollar can become (1/0.10) or $10. If it is 1%, one dollar can become a hundred. As the RR approaches zero, the amount of money that can be created from one dollar approaches infinity.

Our effective Reserve Requirement is zero, and the amount of money banks can create from the existing money supply is effectively unlimited. For this reason I agree with Mason and DiLorenzo that our economic problems have been created not by a savings-glut in Asia but by a money-glut here at home.

One final point: The U.S. is not responsible for the economic policy of Asia. We are only responsible for our own policy. If the Asians do something that messes us up (I'm not saying that they have), we are responsible for tweaking our own policy to improve our position in the world. For us to blame the Chinese, for Greenspan and Bernanke to blame the Chinese, is to avoid our own responsibility to ourselves.

Here's an item I was putting together back before I started this blog. It was for my Google-site. But this was just when I was starting to figure out the difference between a website and a blog. Anyway, I knew this post wasn't meant for the website and I just left it as litter on my desktop. 'Til I found it this morning.

I commented on Aquinum's:

Okay. Say your proposal had been set up 20 or 30 years ago. Say it was in place and working....

But Vince batted that back to me:

Say your proposal had been set up 20 or 30 years ago.

Oh. Well, I put an answer together. A satisfying answer. (You know how it is.) Anyway, I thought my economic proposal ought to be on this blog. So, here it is:

7 July 09 - Today's "Alerts" from Seeking Alpha include this gem:

The post is a mish-mosh of Brouwer-quoting-Krugman-quoting-Bartlett, with some Brouwer-quoting-Bartlett in the mix. And now I'm skimming that soup.

Brouwer opens with an interesting observation:

Despite the fact that most of the existing economic stimulus program has not yet been implemented, a Nobel laureate economist and New York Times columnist and blogger has been advocating a second government stimulus program.

Yeah, the existing stimulus plan has hardly been implemented at all. As of today -- 140 days since President Obama signed the stimulus bill into law -- only about 7.2% of the $787B has been allocated.

(On the little "Stimulus Watch" gadget my son Jerry created for me, we say 7.2% has been spent. Perhaps that's not quite right. Our number comes from VP Joe Biden's recovery.gov site, where he lists it as the total "paid out." However, that site identifies 10 October '09 as the day that "recipient reporting begins." So I'm thinking the "paid out" number counts money distributed from the big bureaucracy in D.C. to smaller bureaucracies in D.C. and elsewhere, government offices that have been drawing up lists of "shovel-ready" projects. I'm doubting that any of that 7.2% has found its way to people with shovels.)

So yeah, as Brauwer says, it's a "fact that most of the existing economic stimulus program has not yet been implemented." And it is obvious to me that this could be the reason we've seen little effect from the stimulus. Brauwer, however, completely misses the obvious.

He has flies in his eyes: Paul Krugman's comments on Bruce Bartlett's article.

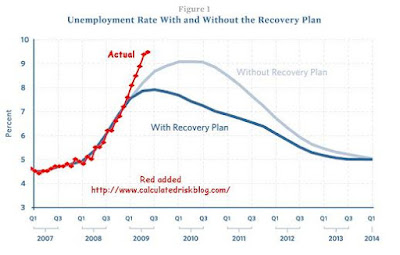

Bartlett says Obama was "much too optimistic" about effects of the stimulus package. He says Obama's economists expected results "almost immediately." And Krugman says "that's totally false." Krugman's evidence is a graph you've likely seen before, showing projected unemployment with, and without, the stimulus.

Now what I see in that graph is a reduction of unemployment projected to begin in the Second Quarter of 2009. I would call that an almost immediate effect of First Quarter activity. So I would say Krugman's evidence shows Bartlett's statement to be true, not false.

But what do I know. Brouwer says "Krugman is quibbling." And then he says, "Wouldn’t it have made sense for Krugman to update the chart to see how much of a positive effect the stimulus program has had?"

Well, no. Krugman didn't post the chart so we could see the most current situation. He posted the chart to prove Bartlett wrong. (It didn't work, but that's another matter.) Looks to me like Brouwer is IM-ing Krugman.

Brauwer has his own agenda. He wants to see the most current results of the stimulus. He wants to see the most current unemployment situation. So, does it make sense for him to post the update?

Well, Idunno. Because it is, as Brauwer says, "fact that most of the existing economic stimulus program has not yet been implemented." But then it might be interesting to look at the results of not implementing the stimulus.

So, Brauwer presents his update. It shows unemployment skyrocketing. Obviously, this recession or depression is a lot worse than we thought, worse than Obama thought, worse than the January predictions.

And then Brauwer says, "At this point, it is clear that the economic stimulus program has not delivered as promised." And he quotes Bartlett: "Another stimulus would be a grave mistake. The first one was justified by extraordinary circumstances. But it must be given time to work. People should not allow their impatience to lead to the adoption of policies...."

Impatience? Give it time to work?? Really??? Unemployment is much worse than expected. Worse than we anticipated when Congress settled on the $787B number. The recession is worse than we thought, when we thought a $787B stimulus would fix it. So the $787B must be too small to fix this recession.

If a stimulus package is the answer, then it must be sufficient to address the problem or there is no bang for the buck, and the money is truly wasted.

The economic stimulus program has not delivered as promised? But how can Brauwer say this? After all, he points out "the fact that most of the existing economic stimulus program has not yet been implemented." So of course it hasn't delivered.

My God! The whole purpose of stimulus spending is to create an immediate surge of economic activity. Immediacy is the essence. One cannot wait while the economy declines further. For then, to achieve the equivalent effect, the surge must be even bigger.

Immediacy is the essence. Allow me to close, as Brauwer closes, by quoting Bruce Bartlett:

…just 11 per cent of the discretionary spending on highways, mass transit, energy efficiency and other programmes involving direct government purchases will have been spent by the end of this fiscal year. Even by the end of 2010 less than half the funds will have been disbursed and by the end of 2011 more than a quarter of the money will be unspent.

My friend Aquinum has written:

"Possessing physical dollars is like having equity in the economic output of the United States of America, and has no credit risk associated to it.... To summarize: physical paper money is equity. Bank deposit money is backed by debt...."

Paper money is equity. This is an astounding observation. Aquinum refers me to Unqualified Reservations for a technical definition of money-as-equity:

Any financial instrument is one of three things: a deed of ownership of some good (a title), a liability to fulfill some obligation, possibly contingent (a debt or option), or none of the above (equity). The dollar is equity....

One of the great things about Seinfeld was that they often had two conversations going at once. Jerry and Elaine would be talking about something, and George would add something irrelevant. They would continue their conversation, and George would continue inserting his own, unrelated thoughts. It was funny because it caricatured a thing that happens all the time.

In 1983 I bought a new little car for $5000. In 2007 I bought a new little car for $12,000. That's 240% of the 1983 price, an increase of 140% in 25 years. I worked it out in Excel: With compounding, it's a 3.715% annual rate of increase.

That reminded me of something Milton Friedman said in Money Mischief:

As Forrest Capie points out in a fascinating paper, it took a century for the inflation in Rome, which contributed to the decline and fall of the empire, to raise the price level "from a base of 100 in 200 AD to 5000... -- in other words a rate of between 3 and 4 percent per annum compounded."

Fall of Rome.

Printing money causes inflation. Know what? Expectation causes inflation, too.

Central bankers and I say that in this economic crisis, printing money will not cause inflation because nobody is spending. But we forgot about expectations.

Suppose the central bankers are right: Suppose there isn't enough "chasing" for inflation to be caused by "too much money chasing goods." Well, if people don't buy that story, we can get inflation anyway. If people insist on thinking we're gonna get inflation because the Fed is printing money, then we'll get inflation even if the central bankers are right. But it won't be printing that drives prices up. It'll be expectations.

I admire Paul Krugman because he is so much more reasonable than most of his critics. We are here today to review an opinion piece of his, something my wife found in our local paper. You can find it here.

Krugman says we've been in this situation twice before, and says both times policymakers "stopped worrying about depression and started worrying about inflation" much too soon. He says that's happening again now. He says there's no need for worry about inflation, because "a rising monetary base isn't inflationary when you're in a liquidity trap."

Krugman also says something I totally agree with: "What about all that government borrowing? All it's doing is offsetting a plunge in private borrowing -- total borrowing is down, not up. Indeed, if the government weren't running a big deficit right now, the economy would probably be well on its way to a full-fledged depression."

Now I'm gonna be explicit about this, so read slow: I agree with Krugman that "all that government borrowing" is not the problem right now. But of course it's a problem. It's part of the central problem: All that borrowing... All that lending... All that debt. The central problem -- debt -- is the problem that got us where we are today. But now that we're here, we have a new problem: namely, the threat of depression. The moment this new problem arose it became a thousand times more significant than debt.

If something isn't done, and done soon, there's gonna be one wicked inflation. It's already trying to break out. A bag of Milky Way bars was 99 cents last week. This week it's $2.50. That's jaw-dropping wrong.

Bernanke-Fed won't keep rates too low for too long

2009-04-14 19:08 (UTC)WASHINGTON, April 14 (Reuters) - Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said on Tuesday that the U.S. central bank, which has cut interest rates almost to zero, will definitely reverse its monetary policy at some stage to prevent inflation.

The Fed will 'make sure we do raise rates at an appropriate time and make sure we don't leave rates too low for too long, because it can have adverse effects, at least on inflation,' Bernanke told students at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

quoted from http://www.xe.com/news/2009/04/14/356969.htm

So if everything works out according to plan, we restore the economy back to where it was a year or two ago, before everything fell apart.

Well, then we'll be in trouble. Because if we get back to that time again, we will only be ripe for economic collapse again. Bernanke must know this. Central to the concept of fixing the economy is the notion of fixing the problem that created the problem. Not just fixing consequences we don't like.

Ben Bernanke has the most thrilling job in America, and I think he's the right man for the job. But I hope he's keeping secrets. Because the things he said at Morehouse College are just more of the same numb-brain, defunct-economist crap that got us into this mess in the first place.

Well, it's happening. And the Internet response to these printing press releases is largely what you'd expect: Inflation, inflation, inflation. I have a different take.

In the June 10, 1934 edition of The New York Times there appeared an article by John Maynard Keynes. Keynes wrote in part:

I don't know how Keynes came up with his $400 million figure. But it is easy enough to scale his number up to fit the current national income.

Here are some bold words originally from 5/25/09; my first blog post.