What follows next in the Two Minds post is a series of graphs that seem not to show what Two Minds wants us to see in them. I will not show most of these.

TwoMinds shows a graph of declining employee compensation, and points out that the graph does not show a failure to cut taxes and does not show "A failure to print enough money or extend enough credit". These criticisms are irrelevant.

Apart from that, I want to point out that TwoMinds, like everyone else, refers to money and credit as a single thought. That is the problem.

That is the problem. That is how finance got so big. We equate money and credit. We think of them as interchangeable. We think of them as two words for one concept. They are not the same. Money is money. Credit is money that costs money to use. This is not a difficult concept to grasp. But no one wants to look at it.

TwoMinds' second graph shows a long-term increase in the "civilian employment-population ratio" ending with the recession of 2009. And his comment is that "employment is declining."

Assuming the employment-population ratio is a good measure of employment, TwoMinds' great insight here is that employment fell during the recession. What I see on that graph is that an increasing portion of the population had to work (or anyway, was working) and then we had this depression...

His third graph I'll show ya:

Meanwhile, after-tax corporate profits have steadily climbed to nearly 10% of the entire national income:

Climbed to nearly ten percent. I think it is more reasonably called nine percent, at least if you imagine a trend-line through profits since 1980.

Meanwhile, a trend-line through the 1938-1965 years would range between 6 and 7 percent. Since 1980, profit was in that same range until some time after 2000. And only in the most recent years do we see profits actually climb to two or maybe three percentage points above that early-years level. I don't like the way TwoMinds looks at graphs.

I also don't like the way he breaks up the post-WWII period into three stages like it was a Saturn V rocket. There was no sudden stage-three solution of credit and speculation. Credit use was growing consistently for the full post-war period. Credit started causing problems, or they became obvious anyway, in what TwoMinds shows as stage two, the "crisis of energy and stagflation". But energy costs and stagflation were simply the first visible signs of the excessive reliance on credit.

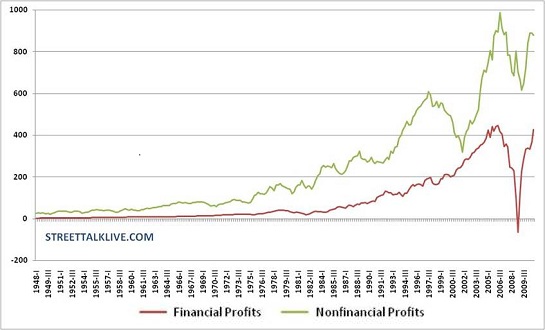

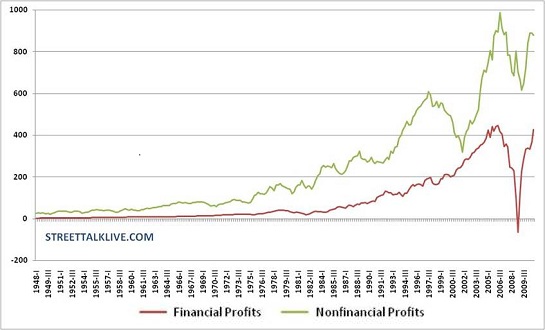

TwoMinds' next graph shows trend-lines for financial and non-financial profits. The graph shows credit use growing consistently for the full post-war period:

Note the recent rise of finance-based profits:

Things go up. Non-financial profits go up from the beginning of the chart. So do financial profits, but it is harder to see. TwoMinds seems to think financial profits only start to go up, starting in the middle of the chart. "The recent rise," he says.

He presents the increase in financial profits as a problem. He does not point out that the increase in financial profits was a solution encouraged by Reaganomics.

But I said financial profits were increasing for the whole post-WWII period. Yes. But Reaganomics encouraged it? Yes. It was thought that we needed more credit for growth. The early post-war years seemed to show this to be true.

By the 1970s, accumulated debt was causing problems. But nobody blamed credit-use for that. We blamed OPEC and their oil. We blamed baby-boomers and (presumably) their horny parents. We even blamed Japan. Remember?

By the 1970s, the costs of debt were hindering economic growth. But nobody looked at it from a cost standpoint. Policymakers knew we needed more growth and, to get it, we needed more access to credit. So, that was one of the biggest themes of Reaganomics: to make it easier to use more credit. And finance grew. It was the only way to stay on the exponential debt-growth curve.

Not that there's anything right with that.

By the 1970s, accumulated debt was causing problems. But nobody blamed credit-use for that. We blamed OPEC and their oil. We blamed baby-boomers and (presumably) their horny parents. We even blamed Japan. Remember?

By the 1970s, the costs of debt were hindering economic growth. But nobody looked at it from a cost standpoint. Policymakers knew we needed more growth and, to get it, we needed more access to credit. So, that was one of the biggest themes of Reaganomics: to make it easier to use more credit. And finance grew. It was the only way to stay on the exponential debt-growth curve.

Not that there's anything right with that.

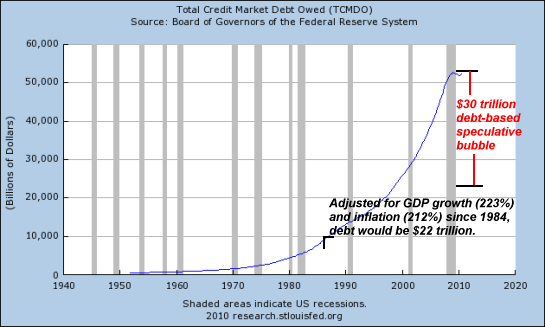

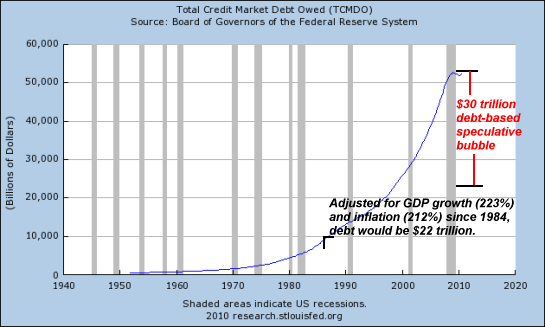

TwoMinds' next graph is his funniest one. He shows TCMDO, total debt, with its relentless exponential increase. He puts some words on there that mean nothing to me, and in red he indicates that the top half of the exponential curve is a "speculative bubble".

This chart leaves no doubt that the engines of the past 30 years "growth" and "prosperity" have been credit and credit-fueled speculation:

You don't break it up that way. The increase in debt shows one long, continuous trend. One trend. If you let debt increase exponentially, you're gonna get speculation. You're gonna get financial profits. You're gonna see financial costs in the non-financial sector. You're gonna see those costs hurting the non-financial sector. And you're gonna see people respond to that by moving more of their money into finance.

You don't draw a line through the middle of that, and say This part is speculation.

TwoMinds' conclusion:

Add all this up and you have to conclude the final crisis of finance-based advanced Capitalism is finally at hand. All the "fixes" that extended its run over the past 70 years have run their course. Life will go on, of course, after the Status Quo devolves, and in my view, ridding the globe of financial predation and parasitism will be a positive step forward.

The real solution is to understand advanced finance-based global Capitalism will unravel as a result of the internal dynamics described above, and be replaced with an economic and political Localism that I describe in my new book An Unconventional Guide to Investing in Troubled Times. I don't claim these ideas are unique to me; many others have described the same dynamics and historical trends.

The real solution is to understand advanced finance-based global Capitalism will unravel as a result of the internal dynamics described above, and be replaced with an economic and political Localism that I describe in my new book An Unconventional Guide to Investing in Troubled Times. I don't claim these ideas are unique to me; many others have described the same dynamics and historical trends.

TwoMinds does not show that all the fixes have run their course. He identifies things that went bad since the recent recession, and things that went bad after Reaganomics was put in place, and he asserts that now the end is near. This is not economic analysis.

This is sad:

The real solution is to understand advanced finance-based global Capitalism will unravel as a result of the internal dynamics described above, and be replaced with an economic and political Localism...

Economic and political localism. A new Dark Age.

6 comments:

You don't break it up that way. The increase in debt shows one long, continuous trend. One trend.

Yes you do, and no it doesn't.

Cheers!

JzB

Art you might find some of the graphs in the AmpedStatus Report interesting

Analysis of Financial Terrorism in America

Quote:

Snapshot: According to most recent Census Bureau data, from 2005 – 2009, average US household wealth declined by 28%. This represents a loss of $27,000 per household. Currently, at least 62 million Americans, 20% of US households, have zero or negative net worth.

The Census figures cited above are based on statistics that have been consistently proven to be lowball estimates.

TwoMinds, like everyone else, refers to money and credit as a single thought. That is the problem.

No, the problem is that they don't do this. They don't think of money as credit/debt.

That is the problem. That is how finance got so big. We equate money and credit. We think of them as interchangeable. We think of them as two words for one concept. They are not the same. Money is money. Credit is money that costs money to use.

Backwards. And too complicated. So close, yet so far. Money is a form of credit/debt. Transferrable, quantified credit/debt. They aren't the same thing. The concept of Money is a refinement of the concept of Debt. Money is "Mammals" Credit/Debt is "Animals".

"Credit is money that costs money to use" is the incorrect, incoherent, tragically common belief now, something that nobody should believe, not a truth that people avoid. I have a credit card. I use it to spend. I convert/exchange my credit/debt into recognized transferable, bank credit/debt. I drop dead, completely broke. It didn't cost me any money to use that card. I didn't pay any interest. Not even any principal. The bank got screwed, ha-ha.

We equate money and credit. We think of them as interchangeable. No, institutions MAKE them interchangeable, which is why we frequently equate different forms of money and credit, sometimes incorrectly.

Banks MAKE my credit card debt equivalent to money. The government MAKES bank credit equivalent to state money by SAYING SO: Acceptance for taxes, discount window access, deposit insurance.

Interest is a sideshow, a derived concept extraneous to fundamental understanding. (And is then better understood inversely, as discounting). What is of primary importance about money (& debt) is who has it & who issues it. Who holds the string, who is pulled by the string.

(This has been a Calgacus Broken Record production.)

Calgacus, you are being a little bit disingenuous here.

Money issued by the government can be considered as a tax credit. Therefore money created by government spending is a debt owed by the government (the community at large) to the private sector which has provide a service to the government (the community at large). The government pays back its debt when it receives taxes from the private sector (this appears counter intuitive, but that is how it is)

On the other hand, debt created by the private banking sector, is also money, but here, the principal and interest is owed to the private banks.

Art,

what do you think would happen if there were no private banks, but rather the banks were owned by the government (the community at large?) and loans and interest were given in the standard way?

Dunno, Clonal. People would complain, probably :)

People argue now about whether the Federal Reserve is government or non-government. Everybody re-defines it so suit their argument. Same with money and credit and debt.

Calgacus, you are being a little bit disingenuous here. How? What did I say that was inconsistent with or substantially different from your comments?

On your question to Art, the answer is nothing, structurally, because that is essentially the system we already have. Private banks can be considered as government officials/satraps at local bureaus of engraving & printing & loan-making, who merely work to enrich themselves by skimming off a few of the incoming notes repaying the loans.

The question is whether having pretend-private banks leads to better investment choices, increases corruption etc. IMHO there might be some small scope for pretend-private banks, but the corruption & instablity attending them suggests a strong domination by explicitly governmental banking.

Post a Comment